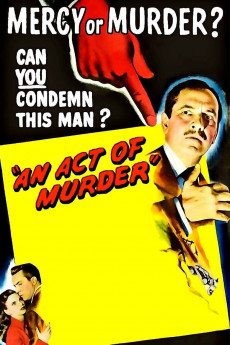

Here Fredric March plays criminal court judge Calvin Cooke who has a reputation as a sort of "hanging judge" so that he has earned the nickname of "old man Maximum". Edmond O'Brien plays a defense attorney arguing a case before the judge. While O'Brien's character looks at the spirit of the law, Judge Cooke looks only at the letter of it and it is obvious from the opening court scene that the two do not like each other. What do they have in common? They both love the judge's only daughter, Ellie.

Now this doesn't mean that the judge is a bad guy. He likes his community, adores his wife of twenty years (Florence Eldridge as Catherine Cooke),and loves his daughter.

But more trouble is afoot than just a suitor for his daughter's hand that the judge dislikes. His wife Catherine has been having headaches, dizziness, and has been dropping things due to numbness in her hands. She confides in a friend who also happens to be a doctor that she has "a friend" with these symptoms, and the doctor sees through her ruse and says that she should come to his Philadelphia office the next day for a check-up. She does that, but lies to Calvin and says she is going shopping.

This is where I do some head scratching. The news is bad - Catherine has a type of inoperable brain tumor that means a certain and painful death. The doctor tells Catherine that everything is fine. Who does he call? After sticking a cancer stick in his mouth to relieve the stress (????) the good doctor calls Calvin, her husband and tells HIM the truth. They both decide to not tell Catherine, the ACTUAL patient, the truth. Later when Catherine finds out, she decides not to talk about it either, even though by the way she found out she must know that her husband knows. Why isn't anybody talking to anybody about this woman's illness? Everybody just goes on pretending. Maybe this is the way it was 60 years ago, and that is one reason I love classic film - it gives you real insight into a bygone era about how people handled life, in this case illness, the fact that doctors routinely smoked, that grown daughters lived at home and pretty much went from the custody of their fathers to their husbands, and that it was acceptable for a policeman to shoot a dog that had been run over by a car in plain view of the general public - a mercy killing. This last incident happens as the judge is walking down the street to get pain medicine for his wife that just isn't doing the job. The implication is that mercy killing is on the mind of "old man Maximum" too. How will all of this work out? Watch and find out.

Even though all of the characters in this film are basically "good people" with good intentions, you could almost classify this one as a noir, because there are no easy answers, no possible way to a happy ending. I've seen a restored version of this film on Turner Classic Movies in the last year, so I wish Universal would find some way to get it out to the public. The questions the film raises are still relevant today. Highly recommended.

An Act of Murder

1948

Action / Crime / Drama / Film-Noir

An Act of Murder

1948

Action / Crime / Drama / Film-Noir

Keywords: judgeeuthanasia

Plot summary

Judge Cooke, good husband and father, is known in court as Old Man Maximum. Cooke's daughter loves defender Dave Douglas, who hates Cooke's attitude toward defendants. Cooke's life shatters when he learns his wife has terminal brain cancer; as her pain worsens, he begins to consider mercy-killing, but that would place him in the position of a defendant.

Uploaded by: FREEMAN

Director

Top cast

Tech specs

720p.BLU 1080p.BLUMovie Reviews

One of my favorite Fredric March performances, and an unfairly forgotten film

Excellent but it loses its way towards the end.

I watched "An Act of Murder" because I love the actors Frederic March and Edmund O'Brien. Both were Oscar-winning actors who were not exactly handsome (especially as they aged) and managed to give one impressive performance after another over the decades. Sadly, however, despite having two excellent stars, the film lost its momentum towards the end.

When the film begins, March plays a tough-as-nails judge and O'Brien a bleeding-heart defense attorney. The two don't like each other all that much--and late in the film, O'Brien's character comes to the judge's defense when he's on trial for a mercy killing. In between is the part of the film I loved most--and which is totally obscured by the ending which is filled with speechifying and some bizarre behavior by March's character. It's a shame, as the idea of mercy killing and medical ethics are really interesting topics and it's pretty amazing to see them talked about in the 1940s, as usually films deliberately avoided this back in the day.

A film that has stood the test of time but at the time wasn't ready for a serious topic of discussion.

History changes film, and often, film changes history or at least the public's perspective on serious issues. After World War II ended, Hollywood really jumped on the bandwagon dealing with serious issues like mental illness, alcoholism and various other addictions. There had been films before about spouses killing each other, but never for a reason like this. This is more an act of love than an act of murder, because when you meet Florence Eldridge, the first thing you will think when you find out that she has a terminal illness that will bring her great pain before she passes away from it is "No, not her!" Yes, even a fictional character can bring on that emotion to an audience, because she is a representative of everything we believe a great person should be, irregardless of gender-loving, loyal, tender and funny. Husband Frederic March is another story, at least in his career as a very strict judge who only follows the letter of the law, that is until he must break it to be noble.

When we first see March, he is on the bench, but March's Judge Cooke is no Judge James Hardy of the long-running MGM "Andy Hardy" series, dispensing justice with wisdom and concern. March is the type of judge that in a film noir or Boris Karloff horror movie would have the defendant vowing revenge. In his home life, March is quite different, judging based on the circumstances and the heart within the matter, and it will take a major slap in the face for him to wake up to see that justice isn't really justice if it doesn't consider all the facts and all the details which lead up to a criminal action being made. Eldridge has been suffering from serious headaches that create violent spasms, the type that no aspirin can cure and that no comforting or hugging or spoiling can fix.

When March learns from long time family doctor Stanley Ridges that her illness is terminable and will bring on a painful end, he is at his wit's end of what to do and decides to take her on the long planned second honeymoon as a way of bracing her for the end. Before they leave, Eldridge has a violent spasm in her bathroom that causes her in convulsions to break the mirror, and on their seashore vacation, all seems well until they go into a hall of mirrors and she breaks out in panic when the spasms return and she can't find her way out. March realizes that something has to be done to end her suffering, especially after a scene where an injured dog is shot by the police in public view to end its suffering. But Eldridge discovers the truth, and realizing that her suffering is making her husband suffer as well plans her own strategy. Twists have March, now a widow, turning himself in for murdering his wife, and daughter Geraldine Brooks and lawyer Edmund O'Brien (who is in love with Brooks yet opposed to much of March's courtroom methods) must step up to help him against his will.

Yes, there are obviously holes in the plot line, and often, March isn't deserving of audience sympathy. But as the details of the story show his genuine, undying love for Eldridge, it becomes impossible not to root for him to be exonerated with at least a finger wagging from the judge (Will Wright) who is sitting on the same bench that March shares with him. Award worthy performances and an excellent script (in spite of the holes) are aided by very good photography and editing. Eldridge, well respected for her stage work but underrated for her film work, was definitely award worthy here, and at least the story allows the audience to not suffer along with her too much. Brooks and O'Brien are not given the benefit in their characterizations of being as well developed as March and Eldridge, but this is not their story. Several TV movies dealt with the same subject years later, but as far as the issue of mercy killing is concerned, this film remains way ahead of its time, and deserves to be remembered for that, especially for March's moving speech at the end where he basically judges himself guilty.