I thought I knew a little something about twentieth-century Polish history, but while watching a screening of the 1957 classic film "Eroica" at Chicago's Facets film archive, I could barely keep up with the complicated ideas swirling around the role of Poland in World War II and its relationship to its neighboring countries, especially communist Russia, Nazi Germany, and Hungary. Directed by Andrzej Munk, "Eroica" has been called "a truly great film and one of the key works of postwar Polish cinema..., a fine example of the Polish myth of romantic heroism."

Alluding to Beethoven's "Eroica" symphony, the film's first movement is a look at the Warsaw Uprising through the eyes of a drunken black marketeer; in the second movement, Polish prisoners in a German camp determine that the heroism of their comrade is a farce. Without a knowledge of what this film is satirizing, it is difficult to understand the dark, very dark, humor in this cynical movie about corruption. Watching the film is like having a two-part nightmare. One of the POWs tells a camp newcomer when he complains about the meager food provisions: "Powdered milk, powdered eggs, powdered coffee, powdered people," a reference to the Nazi extermination camps that littered German-occupied Poland during World War II.

There is as much dark humor about ordinary people as there is about politicians, but my favorite line in the whole film, perhaps because it rings true in the current American political climate: "I don't trust businessmen; their preservation instinct is high."

"Eroica," wrote Pauline Kael, "is a true black comedy and one of the few modern movies that has something relevant to say about the modern world." Fortunately, Facets' owner, the late Milos Stehlik, was on hand after the film to help the audience understand how it "takes down socialist realism mythology" and really fueled the disenchantment with communism that led to the great literature, art, and films that many Polish intellectuals created in rebellion and into the Solidarity movement and the 1989 overthrow of communism in Poland.

By the end of the movie, however, I was left wondering why it seemed so cynical about the human condition as to see no redemption in those people who do show heroism, bravery, and love under the worst possible conditions. Isn't the very making of this film a contradiction of its maker's cynicism? Nevertheless, Eroica is essential viewing for cinema buffs who want to understand the dark road that cinema traveled after the Second World War.

Keywords: world war iiwarsaw uprising

Plot summary

Two sketches covering episodes from the World War II. In the first novel, "Scherzo alla polacca", a shrewd son, trying to preserve his skin, ultimately becomes a hero and finds a reason for fighting. He initially tries to avoid underground training to avoid the Warsaw uprising. His drunkenness, disregard for safety and cowardice when sober stated with humorous effect come out as something sane in the world gone mad. His will to survive is more acceptable than any desire for heroic death. The second novel, "Ostinato lugubre", details a hopeless attempt at escape from a prison camp by a man who can no longer stand the confinement and idiocy of the professional soldiers trying to keep up the military preneses in prison. Nevertheless, his escape boosts the morale of his fellow prisoners, while the "escapee" lies hidden from Germans and comrades alike."

Uploaded by: FREEMAN

Director

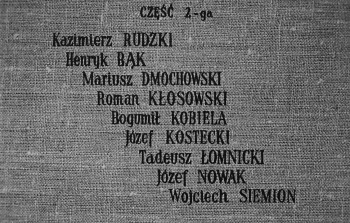

Top cast

Movie Reviews

A Post-World War II Masterpiece That Still Resonates

Two Great Stories of Wartime Poland

I personally think you have to be Polish or have studied a great deal of Polish history during World War II and, perhaps, the cultural history of Poland to understand everything in this film. But, it is a set of brilliant dark commentaries on men in time of war. In our first film, Scherzo alla Polacca, a man runs away from his duty during the Warsaw Uprising. He has been a selfish man and does not adapt well to sacrifice, but he reluctantly makes an attempt to do something for the cause without much real effect. This is dark comedy at its best and pokes fun at Hungarians as well as poking fun at opportunists during wartime.

Our second film, Ostinato Lugubre, tells the story of a group of Polish Officers encamped in a German Prisoner of War camp and details the everyday life of the men as they deal with their feelings, lack of privacy and their affection for one man who escaped. Did he really escape? This is the plot point that holds this story together so well. We witness brilliant acting and a deeply moving script.

This is considered one of Munk's great masterpieces and deserves a chance to be released on video. This was part of a festival at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Laughter in the Dark

A fascinating contrast with many other Polish films about the Second World War. This film consists of two separate stories. One, Scherzo alla Pollaca, set in the Warsaw rising, features an venal, opportunistic character- a former black-marketeer, it's made plain- who becomes a hero in spite of himself. None of the characters are very sympathetic, none are very villainous- the "hero's" wife flirts with a handsome Hungarian officer, the Hungarians want to change sides at the right opportunity, the Polish resistors practise drill in an air raid, a German soldier hauls the "hero" out of a refugee column just to make him carry an old woman's worthless possessions, a German tank creeps up behind the hero to surprise him by a canal and then goes away, raucous laughter echoing from its hull. In the end, even though the rising is defeated and his messages pointless, the hero leaves his penitent wife and returns to Warsaw and probable death.

The second part, Ostinato Lugubre, is ostentatiously grimmer. Set in a PoW camp in the Alps in the winter of 1945, two new prisoners, from the Polish Home Army, are admitted. Everyone else in the camp has been there from 1939 and they have been psychologically deformed by captivity and the constant presence of others. The camp has one hero, Zawistowski. who escaped and so saved their honour. The only trouble is, he didn't escape but hid from the Gestapo in the hut roof, where he is slowly dying. His friends feed him inadequately and hide his coughs by distracting the others. The other officers grate against one another- shut themselves away, literally or mentally, enforce absurd prewar customs, make insane wagers with one another. In the end, Zak, one of the most disturbed of them all, walks out of the hut in an air raid and is shot by a guard and Zawistowski dies in the hut roof. One of his friends, an artist, arranges for his body to be taken away hidden in the hut's boiler so that no more of the prisoners know he did not escape.

Both stories are presented as meaningless and futile anecdotes and both could as easily be comedies or tragedies. The second one, especially, has Munk's fascination with faces looked at close to, is more typical of the way we see him.