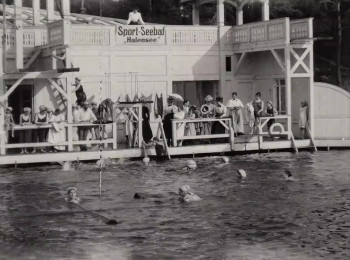

From the second day of the 39th Pordenone Silent Film Festival, the programmers, this time via the EYE Film Institute in Amsterdam, again decided to open the day with virtual tourism for the "armchair traveler," as they put it, after the first day's "The Urge to Travel" series of travelogues. This one, "The Brilliant Biograph: Earliest Moving Images of Europe (1897-1902)" features a collection of films of about a minute, more or less, each from the period of early cinema. Again, it's a tour back in time, as seen today, as well as to various lands. All of the films are 68mm wide film, as devised by William K.L. Dickson after he had already worked on the development of motion pictures for Edison and, then, with the Lathams--important figure in the invention of movies that guy. He even appears in at least one of the pictures, seemingly with his family, as they feed pigeons in Venice in 1898. He might, or other filmmakers, at least, appear in another film, which features a Captain Deasy promoting Martini cars, in Switzerland, 1903, as well as a second filming crew at the scene.

Reportedly, due to the 68mm film not being perforated (Charles Musser, "The Emergence of Cinema," informs that the film instead employed a continuously moving friction-feed device to move the film strips),the footage hadn't been restored or seen since back when it was first made and exhibited--until recently thanks to EYE and digital restoration. Receiving an 8k transfer, from the wide film remarked upon for its clarity and capturing of detail, the films here, indeed, do look great even when streaming them at home. Even the scratches that appear in some of them are crisp, with only one film featuring brief but prominent decomposition. There are also square-shaped light marks in the middle of images, which the preservationists have explained are contact points from the roller projection system to produce and project the films back then. In their time, too, the films may've been seen individually in the flip-book-like Mutoscope, for which the wide-film process may've originally been intended, or projected on bigger screens than other early-cinema exhibitions allowed (as pointed out by Deac Rossell, "Living Pictures: The Origins of the Movies") due to that 68mm format.

The program is split into five sections: 1) Daily Life, 2) Riding the Waves, 3) Greetings From..., 4) Moving Forward, and 5) Body in Motion, covering actuality films of routine living in Europe (the UK and the Netherlands receive the most coverage, it seems),seaside views of boats and ships, scenes of famous sites, other showcasing innovations of modern times, and, finally, views of people in motion to go along with the motion-picture technology, including vaudeville-type acts and dancing. I like how they move from chapter to chapter with phantom-ride films, such as those where a camera is attached to a moving train, in between the sections. The most striking is surely the Conway Castle one, which offers the added spectacle of a hand-color print, which I don't recall having seen much of in phantom-ride films (dance films, trick films and fictional narratives is another story). The music by Daan van den Hurk aids the pacing, as well.

It was a fascinating program. I love these early cinema compilations, such as "The Lumière Brothers' First Films" (1996),"The Lost World of Mitchell & Kenyon" (2005) and others, including my research on the Brinton Collection, the collection of which has been a feature of an annual film festival of early cinema in a tiny Iowa town, as depicted in "Saving Brinton" (2017). Anyways, it's time for me to go back to imagining I'm in Pordenone, Italy so as to be transported to China's past in the festival's second-day feature, "Guofeng" (1935).

EDIT (10 November 2020): This is a response to the "other review" that ironically begins repeating "yes" four times before insulting mine as "long winded" and that continues to condescend to be writing "for everyone" what is a stupor of impressions and conjectures that ends with a primacy claim for the Lumière brothers, which is especially misplaced given that the achievements of other film pioneers like Dickson had just stared them in the face. Why did it take so long to create "The Brilliant Biograph," they ask before dismissing my review; I provided an answer to that very question at the start of my second paragraph.

The Brilliant Biograph: Earliest Moving Images of Europe (1897-1902)

Action / Documentary / History

The Brilliant Biograph: Earliest Moving Images of Europe (1897-1902)

Action / Documentary / History

Plot summary

Eye Filmmuseum and the British Film Institute present a compilation film of newly-restored rare images from the first years of filmmaking. Immerse yourself in enchanting images of Venice, Berlin, Amsterdam and London from 120 years ago. Let yourself be carried away in the mesmerizing events and celebrities of the time, and feel the enthusiasm of early cinema that overcame the challenge of capturing life-like movement.

Uploaded by: FREEMAN

Director

Top cast

Tech specs

720p.WEB 1080p.WEBMovie Reviews

Dancing, Phantom Rides and Other Actualities

Yes

Yes, Yes Yes. Why did it take so long to create a documentary on something that has been the norm for over 100 years?

Forget about the other review. It was long winded and meant only for the reviewer, blowing their own trumpet. My review is for everyone.

Watch and enjoy. I've longed for someone to show the infancy of moving pictures.

It will go over the head of most because they will not or cannot comprehend, how motion picture made it's start, to where it is now. Only a very few know that, seeing a train "moving" on a screen caused the audience to believe, that the train was real, and they thought they were in danger.

The people pf today live in the land of smartphones, and don't know of dial up phones, used just to converse. They think a phone is a TV.

Everything starts from somewhere. What is now available on phones, laptops, tablets, TV streaming servies, all started from the Luimere Brothers.