This silent epic should be much better known than it is. It is based on the plot of an opera of the same name, describing a real revolt in Naples in the 17th century. The title character, Fenella, is the fictional mute sister of Masaniello, one of the key historical figures in that revolt. Fenella is played by ballerina Anna Pavlova, in her only full-length film. Unfortunately, Pavlova's broad acting style is better suited to ballet or opera, playing to the crowds in the back, rather than to the more intimate medium of film. On the other hand, she was one of the most famous dancers of her day, and this film is one of the very few records left to modern audiences to see her in motion.

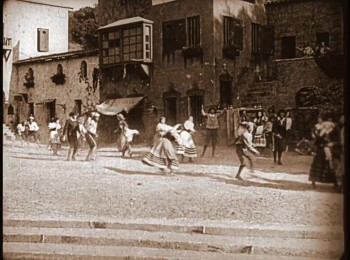

Despite her top billing, the film does not hinge on Pavlova, and for the most part, this is really a beautifully made film. This was a Big-Budget picture when it was made -- the ornate costumes and sets are stunning. The scenes of the revolt are chaotic, real, and compelling.

Some of the actors, including Pavlova, as well as a few of the supporting roles, are guilty of the sort of overly theatrical acting associated with early movies. For the most part however, the acting is natural. I was particularly impressed by Douglas Gerrard, playing a nobleman who seduces and abandons Fenella in favour of his aristocrat fiancée.

Surprisingly, the film also works as a "silent musical". The early part of the movie includes a number of dance numbers showing a variety of styles, and not just those featuring the film's "star", Anna Pavlova. I would recommend this film for all of its parts.

The Dumb Girl of Portici

1916

Action / Drama / History / Romance

The Dumb Girl of Portici

1916

Action / Drama / History / Romance

Plot summary

In the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, the Spanish Viceroys who had been sent to rule Italy, grew rich from the heavy taxes imposed on the poverty-stricken people. From the Kingdom of Naples alone, Spain extorted an annual revenue of fifteen millions of dollars. A tax was placed on fish, flour, poultry, wine, milk, cheese and salt, making bare existence a bitter problem. Fenella, "The Dumb Girl of Portici," as history describes her, was an unusually romantic character at this period. That she came of an unusual family is proven by the fact that her brother and guardian, Masaniello, although, only a poor fisherman, was able to sway the people that he reigned as king while the revolution was at its height. Unlike their neighbors, are the widow Rilla and her worthless brother, Pietro, who is in love with Fenella. A new tax is levied on fruit by the Duke d'Arcos, Viceroy of Naples. The people become embittered by this added burden and Masaniello is appealed to for advice. With the help of his friend, Don Francesco, he gives the people wise counsel. Conde, the Duke's younger son, reports their attitude, but the Duke laughs at Conde's tears. The elder brother, Alphonso, realizes the seriousness of the situation. Disguising as fishermen, he and Conde go to the Market Place to investigate. Here Alphonso first meets Fenella. The dumb girl, needing flour and not possessing sufficient money to pay for it and also meet the heavy flour tax, smuggles a bag of meal into the city by hiding it under her shawl. At the gate, a hole is accidentally torn in the bag. From this escapes a tiny stream of meal unnoticed by Fenella. The tax collector discovers the little trail of flour and soon the dumb girl is under arrest, threatened with fine or imprisonment. Masaniello and Pietro hurry to her assistance, but they have no money with which to pay the fine. Alphonso has watched the arrest of the girl and pays the fine, still keeping his disguise. Masaniello informs Alphonso that, if Fenella had been imprisoned, the government would have paid dearly. Alphonso cannot understand and Masaniello calls his people about him. Eagerly they proclaim him their leader and Masaniello then explains to the young stranger the unjustness of the Viceroy's laws and taxes. Fascinated by Fenella, Alphonso becomes a frequent visitor to the fishing village, neglecting Lady Elvira, his betrothed wife. Alphonso returns to the city, leaving the dumb girl weeping silently. Later, when Masaniello finds her clinging desperately to Alphonso's scarf the story is plain to him. Alphonso has been missed from the palace and Conde sets out in search of him. Having heard of the youth's infatuation for Fenella, the courtier goes at once to Masaniello's hut, where he learns what has happened. Knowing that Masaniello is leader of the people, Conde reports the affair to the duke, prophesying an uprising. The duke laughs at his fears, but is curious to see the girl who has turned his son's head. With Conde's help, the duke plans a trap for Fenella and she is thrown into prison. The Viceroy visits her there. When the dumb girl does not speak in answer to his questions, he thinks it is stubbornness and has her flogged. Masaniello finds his sister has gone and sacrifices everything in his search of her. When he gets behind in the rent, collectors take his furniture as payment. Rilla, the widowed sister of Pietro, in trying to stop them, is arrested and taken to jail. The shock kills Rilla's aged mother and Pietro makes a solemn vow to avenge her death. In spite of this oppression, the people assume a happier mood on the day of the wedding of Lady Elvira and Alphonso and throng into the Market Square in gala attire. Even the guards of the prison celebrate the wedding, enabling Fenella to make her escape. Returning home, Fenella meets the wedding party returning from the church and appeals to Lady Elvira for protection. Lady Elvira, seeing Alphonso's scarf in possession of the fishergirl, questions her and learns the truth. She orders that Fenella be conducted safely home, but Perrone, captain of the guard, intercepts and has the girl taken back to prison. The Viceroy foolishly celebrates the day by increasing the already onerous tax. The added tax is all the people need to incite them to madness. The duke, hearing of the disturbance, sends his soldiers led by Alphonso and Conde to quell the uprising and a fight ensues. The robbers, murderers and the scum of the city leave their hiding place to join the rioters. The first step toward freedom is the blowing up of the Custom House. Then the prison doors are opened and the prisoners, including Rilla and Fenella, are released. The mob, having burned everything in its path, march to the Viceroy's Palace. Fenella, discovering their intention, reaches there in advance and warns Alphonso. The duke takes advantage of her presence and showing her from the balcony of the palace, threatens her life if Masaniello does not quell the disturbance. Massaniello is forced to choose between his sister and the people and chooses the people, demanding their rights. When the mob breaks into the palace, Masaniello rescues Fenella and takes her home. The people proclaim Masaniello their leader and the dictator of all public affairs. Pietro plots with a bandit to get Masaniello out of the way. They give him a slow poison and as the drug gradually takes effect in his system Masaniello is more and more influenced by Pietro and gradually loses all control over the people. Under these conditions, it is a simple matter for a small party of the Duke's forces, under the leadership of Alphonso and Conde, to gather quietly in the secret passage-ways. At a given signal they attack the rioters, driving the wine-mad mob from the palace. Under the shock of the unexpected and disastrous attack, Masaniello regains his sanity. Recognizing in Alphonso his sister's betrayer, Masaniello makes a wild lunge at him, but Fenella has been watching them and it is into her heart that the blade plunges. Wild with grief her brother kills himself. And the broken-hearted Alphonso can only gather into his arms the dying body of the Dumb Girl of Portici.

Uploaded by: FREEMAN

Director

Top cast

Movie Reviews

Silent Historical Epic Deserves to be Better Known

An epic, 1916-style

In early 17th century Italy, Spain rules with an iron hand, imposing heavy taxes on the poor. The playboy son of Viceroy, betrothed to a noblewoman, becomes attracted to a mute peasant woman who is light and lively on her feet (Ann Pavlova). He seduces her, then ravages her out in the woods. His lust slaked, he leaves her, and to make matters worse, his father seeks to permanently remove her from the picture by having her thrown in prison, where she's flogged. Gosh, that sounds more interesting as I type it than how it seemed on the screen.

No expense appears to have been spared on costumes or set design, and the look and feel of the film is that of an epic, 1916-style. The Italian revolt that follows excessive taxation and the ill treatment of the young woman has what seems like hundreds of people swarming in the streets. Unfortunately those scenes go on for too long and are rather monotonous, though in one moment we see the heads of the Spanish on pikes in the square which was rather macabre.

Anna Pavlova, the world-renowned ballerina and future namesake of the cloyingly sweet dessert, makes her only screen appearance here, which on its own probably makes it worth taking a look. We do get some glimpses of her dancing and grace with her body, but unfortunately, the film is dominated by the big action scenes. Perhaps tightened up (it's 112 minutes long) or with more work put in on the characters it would have held my interest more.

Pavlova, Weber, and the Operatics of Two Mute Arts

Conceptually alone, this was a brilliant project for 1916. I was blown away by Guy Maddin's combination of the two silent art forms based on movement of ballet and silent film in the 2002 "Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary," and here's a mega-production from the early 20th century by Universal studios directed by perhaps the most intelligent of reflexive filmmakers of her day, Lois Weber, and starring in her film debut the biggest name in the history of ballet, Anna Pavlova. To underscore the absence of speaking in favor of graceful pantomime and highlight the musical properties in the art, Pavlova plays the eponymous "dumb" role of "The Dumb Girl of Portici," as based on the most-musical of the theatrical arts, an opera. Of course, there isn't the dance-like movements of the camera or emphasis on sex as in Maddin's postmodern film--this was 1916, after all. All the (over)dramatics, however, do build up to an exciting climax that could compete with anything seen in the Italian super-theatrical epics or D.W. Griffith's notorious blockbusters of the day, including some extended dolly and tracking shots.

It should be remembered how respected ballet was back then, too, largely thanks to the Russian prima ballerina Pavlova as its ambassador travelling the world. One may get a sense of it from the films of the era alone--long before "Black Swan" (2010) or "The Red Shoes" (1948). Charlie Chaplin would be the most famous filmmaker known to appreciate ballet, including his dream-sequence homage in "Sunnyside" (1919) to Vaslav Nijinsky. The year after this film, Yevgeni Bauer employed actress and ballet dancer Vera Karalli for "The Dying Swan" (1917),that title being taken from the solo dance originally commissioned for Pavlova on the stage. There are other, if lesser known ballet-inspired pictures scattered throughout the era, e.g. early Danish feature films such as "Ballettens Datter" (1913) and the Asta Nielsen film "The Ballet Dancer" (1911),the Alice Brody vehicle "The Dancer's Peril" (1917),or the Dadaist dance-inspired "Ballet Mécanique" (1924/1925). Of course, film has a long history with dance in general, from its beginnings with "Annabelle Serpentine Dance" (1895) and the many other Loie Fuller impersonators in often hand-colored prints to simulate the Art Nouveau dancer's use of theatrical lighting to affect colorful changes in her swirling silk costume. Another early dance film, "La Biche au bois" (1896),was specifically made to be projected during a stage play. Opera was highly respected and increasingly popular, too. Surely a catalyst for Pavlova's film debut was the introduction of soprano Geraldine Farrar in Cecil B. DeMille's production of the opera "Carmen" (1915). It may've, at least, contributed to Universal recruiting Pavlova with $50,000 up front for the film (putting her in "Chaplin territory as a highly-paid movie star," as Fritzi Kramer of the Movies Silently blog puts it) and her choice to adapt the Daniel Auber opera.

Ballet and opera were more of supposedly-high-brow art, like Shakespeare or revered novels, for filmmakers to integrate in the quest to emerge from an image as lower-class entertainment of nickelodeons and towards attracting middle-class women, believed to be arbiter's of taste, to cinemas. This message of "uplift" was at the heart of the work of a filmmaker like Weber, who was usually credited, as she is here, as one half of a co-directing team of the married ideal with her husband, Phillips Smalley (and regardless of her apparently more dominate actual creative role in the relationship). Indeed, Universal--taking after Rex, Weber's former employer and studio since incorporated into the then-new Hollywood company--included several husband-wife filmmaking teams and appear to have employed more female directors than any other studio at the time. And, Weber was their most important, as well as, reportedly, the highest paid director in the entire business at one point. It's why she was entrusted with the epic that's reported expense was as much as $300,000 (and when the budget for the prior year's "The Birth of a Nation" was a then largely unheard of sum of some $110,000).

As much as I respect the rest of her oeuvre, including "Hypocrites" (1915),"Shoes" (1916) and "Too Wise Wives" (1921),this may be my "new" favorite film of Weber's, because it's purely art. After it, she went back to making the same social-problem films of afore and for which I tend to complain while admiring the artistry of the propaganda. Aside from the size of the production and casting of Pavlova, it somewhat harks back to some of her earlier one-reelers at Rex, which were arguably more about the exploration of art than converting audiences to Progressive Christians. Reflecting on the nature of cinema through statue in "From Death to Life" (1911),twin paintings in "Fine Feathers," reproduced photographs in "A Japanese Idyll" (both 1912) and "How Men Propose" (although that one remains unconfirmed as a Weber film),and mirrors and genre in "Suspense" (both 1913). Much of this formal contemplation continues in Weber's later work, but it tends to be clouded by heavy-handed moralizing.

Here, we just get the intriguing and moving integration of Weber's silent film technique, Pavlova's mute dancing and performance, and John Sweeney's modern score adaptation of Auber's 1828 opera. Appropriately, the film begins with Pavlova dancing in a more-expected traditional ballet form against a black background. From there, Weber opens with too many over-explanatory title cards, but that soon subsides as the picture follows Pavlova's dancelike movements, an emerging tax revolt and the prince-and-pauper masquerade-made love triangle. Sure, Weber could've employed more close-ups, although that wasn't usually her style at the time, and there are nonetheless a fair amount of closer views for a film of 1916 and some good cutting, grand sets and plenty of extras for the climax and its preceding build up, which includes an infant being tossed at a wall and decapitated heads on pikes, as well as nighttime photography and some nice tinting/toning. Plus, those dolly shots to take in all the action. Is it overwrought and acted? Sure, but it's opera combined with two other mute art forms with their own systems of gestures and conventions, and it culminates in a helluva an old-fashioned spectacle of dramatics.

Pavlova's performance has been singled out negatively by some. Kramer points out that she fulfills the trope of "thistledown dames shrieking with delight at squirrels and generally acting like blithering idiots in an attempt to be rustic and delightful," which, yes, is true, but this is a performer best known for running around on her tippy toes in pointe shoes and a tutu pretending to be a swan, and after seeing her home films in "The Immortal Swan" (1935) documentary, which is included as an extra on the Milestone home video, where she surrounds herself with birds and other pretty things, I wonder not only whether her performance in the film matches her public image but also whether it wasn't also a bit true to her real self. Regardless, it's a fair point and part of the grander picture of three old art forms full of old-fashioned conventions.

I do take some umbrage, however, with Anthony Slide's criticism (in his book "Lois Weber: The Director Who Lost Her Way in History") that her overdramatic acting is the film's major drawback, before he continues to state that Weber's supposed hesitancy for close-ups was because Pavlova was too old for the part. What with being in her 30s for a rarely-adapted opera that was almost a century old back then, I guess. Yet, Slide's book does include a nice quotation from her that may best summarize the success of "The Dumb Girl of Portici." "I desire that my message of beauty and joy and life shall be taken up and carried on after me. I hope that when Anna Pavlova is forgotten, the memory of her dancing will live with the people. If I have achieved even that little for my art, I am content."

Thanks to the preservation of a 1920s 35mm nitrate reissue print (with the film already having originally been cut down from 11 to nine reels in between its premiere and general release) at the BFI and a 16mm copy at the New York Public Library's Performing Arts Library, as released on home video by Milestone Films, Pavlova's wish has been fulfilled, and the unique meeting of three old art forms live on.